首页 > 代码库 > Linux and Unix ln command

Linux and Unix ln command

About ln

ln creates links between files.

Description

ln creates a link to file TARGET with the name LINKNAME. If LINKNAME is omitted, a link to TARGET is created in the current directory, using the name of TARGET as the LINKNAME.

ln creates hard links by default, or symbolic links if the -s (--symbolic) option is specified. When creating hard links, each TARGET must exist.

What Is A Link?

Before we discuss the ln command, let‘s first discuss the link command, as well as what a link is and how it relates to files as we know them.

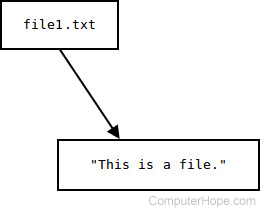

A link is an entry in your file system which connects a filename to the actual bytes of data on the disk. More than one filename can "link" to the same data. Here‘s an example. Let‘s create a file named file1.txt:

echo "This is a file." > file1.txt

This command echoes the string "This is a file". Normally this would simply echo to our terminal, but the > operator redirects the string‘s text to a file, in this case file1.txt. We can check that it worked by using cat to display the contents of the file:

cat file1.txt

This is a file.

When this file was created, the operating system wrote the bytes to a location on the disk and also linked that data to a filename, file1.txt so that we can refer to the file in commands and arguments. If you rename the file, the contents of the file are not altered; only the information that points to it. The filename and the file‘s data are two separate entities.

Here‘s an illustration of the filename and the data to help you visualize it:

Using The link Command

What the link command does is allow us to manually create a link to file data that already exists. So, let‘s use link to create our own link to the file data we just created. In essence, we‘ll create another file name for the data that already exists.

Let‘s call our new link file2.txt. How do we create it?

The general form of the link command is: "link filename linkname". Our first argument is the name of the file whose data we‘re linking to; the second argument is the name of the new link we‘re creating.

link file1.txt file2.txt

Now both file1.txt and file2.txt point to the same data on the disk:

cat file1.txt

This is a file.

cat file2.txt

This is a file.

The important thing to realize is that we did not make a copy of this data. Both filenames point to the same bytes of data on the disk. Here‘s an illustration to help you visualize it:

If we change the contents of the data pointed to by either one of these files, the other file‘s contents are changed as well. Let‘s append a line to one of them using the >> operator:

echo "It points to data on the disk." >> file1.txt

Now let‘s look at the contents of file1.txt:

cat file1.txt

This is a file. It points to data on the disk.

... and now let‘s look at the second file, the one we created with the link command:

cat file2.txt

This is a file. It points to data on the disk.

Both files show the change because they share the same data on the disk. Changes to the data of either one of these files will change the contents of the other.

But what if we delete one of the files? Will both files be deleted?

No. If we delete one of the files, we‘re simply deleting one of the links to the data. Because we created another link manually, we still have a pointer to that data; we still have a way, at the user-level, to access the data we put in there. So if we use the rm command to remove our first file:

rm file1.txt

...it no longer exists as a file with that name:

cat file1.txt

cat: file1.txt: No such file or directory

...but the link to the data we manually created still exists, and still points to the data:

cat file2.txt

This is a file. It points to data on the disk.

As you can see, the data stays on the disk even after the "file" (which is actually just a link to the data) is removed. We can still access that data as long as there is a link to it. This is important to know when you‘re removing files — "removing" a file just makes the data inaccessible by unlink-ing it. The data still exists on the storage media, somewhere, inaccessible to the system, and that space on disk is marked as being available for future use.

The type of link we‘ve been working with here is sometimes called a "hard" link. A hard link and the data it links to must always exist on the same filesystem; you can‘t, for instance, create a hard link on one partition to file data stored on another partition. You also can‘t create a hard link to a directory. Only symbolic links may link to a directory; we‘ll get to that in a moment.

The Difference Between ln And link

So what about ln? That‘s why we‘re here, right?

ln, by default, creates a hard link just like link does. So this ln command:

ln file1.txt file2.txt

...is the same as the following link command:

link file1.txt file2.txt

...because both commands create a hard link named file2.txt which links to the data of file1.txt.

However, we can also use ln to create symbolic links with the -s option. So the command:

ln -s file1.txt file2.txt

Will create a symbolic link to file1.txt named file2.txt. In contrast to our hard link example, here‘s an illustration to help you visualize our symbolic link:

About Symbolic Links

Symbolic links, sometimes called "soft" links, are different than "hard" links. Instead of linking to the data of a file, they link to another link. So in the example above, file2.txt points to the link file1.txt, which in turn points to the data of the file.

This has several potential benefits. For one thing, symbolic links (also called "symlinks" for short) can link to directories. Also, symbolic links can cross file system boundaries, so a symbolic link to data on one drive or partition can exist on another drive or partition.

You should also be aware that, unlike hard links, removing the file (or directory) that a symlink points to will break the link. So if we create file1.txt:

echo "This is a file." > file1.txt

...and create a symbolic link to it:

ln -s file1.txt file2.txt

...we can cat either one of these to see the contents:

cat file1.txt

This is a file.

cat file2.txt

This is a file.

...but if we remove file1.txt:

rm file1.txt

...we can no longer access the data it contained with our symlink:

cat file2.txt

cat: file2.txt: No such file or directory

This error message might be confusing at first, because file2.txt still exists in your directory. It‘s a broken symlink, however — a symbolic link which points to something that no longer exists. The operating system tries to follow the symlink to the file that‘s supposed to be there (file1.txt), but finds nothing, and so it returns the error message.

While hard links are an essential component of how the operating system works, symbolic links are generally more of a convenience. You can use them to refer, in any way you‘d like, to information already on the disk somewhere else.

Creating Symlinks To Directories

To create a symbolic link to a directory, simply specify the directory name as the target. For instance, let‘s say we have a directory named documents, which contains one file, named file.txt.

Let‘s create a symbolic link to documents named dox. This command will do the trick:

ln -s documents/ dox

We now have a symlink named dox which we can refer to as if it is the directory documents. For instance, if we use ls to list the contents of the directory, and then to list the contents of the symlinked directory, they will both show the same file:

ls documents

file.txt

ls dox

file.txt

When we work in the directory dox now, we will actually be working in documents, but we will see the word dox instead of documents in all pathnames.

Symbolic links are a useful way to make shortcuts to long, complicated pathnames. For instance, this command:

ln -s documents/work/budgets/Engineering/2014/April aprbudge

...will save us a lot of typing; now, instead of changing directory with the following command:

cd documents/work/budgets/Engineering/2014/April

...we can do this, instead:

cd aprbudge

Normally, you remove directories (once they‘re empty) with the rmdir command. But our symbolic link is not actually a directory: it‘s a file that points to a directory. So to remove our symlink, we just use the rm command:

rm aprbudge

This will remove the symlink, but the original directory and all its files are not affected.

ln syntax

ln [OPTION]... TARGET [...] [LINKNAME [...]]

Options

Here are the options that can be passed to the ln command.

| --backup[=CONTROL] | Use this option to additionally create a backup of each existing destination file. The style of backup is optionally defined by the value of CONTROL. See below for more information. |

| -b | This functions like --backup, but you cannot specify the CONTROL; the default style (simple) is used. |

| -d, -F, --directory | This option allows the superuser to attempt to hard link directories (although it will probably fail due to system restrictions, even for the superuser). |

| -f, --force | If the destination file or files already exist, overwrite them. |

| -i, --interactive | Prompt the user before overwriting destination files. |

| -L, --logical | Dereference TARGETs that are symbolic links. In other words, if you are trying to create a link (or a symlink) to a symlink, link to what it links to, not to the symlink itself.. |

| -n, --no-dereference | Treat LINKNAME as a normal file if it is a symbolic link to a directory. |

| -P, --physical | Make hard links directly to symbolic links, rather than dereferencing them. |

| -r, --relative | Create symbolic links relative to link location. |

| -s, --symbolic | Make symbolic links instead of hard links. |

| -S, --suffix=SUFFIX | Use the file suffix SUFFIX rather than the default suffix "~". |

| -t, --target-directory=DIRECTORY | Specify the DIRECTORY in which to create the links. |

| -T, --no-target-directory | Always treat LINKNAME as a normal file. |

| -v, --verbose | Operate verbosely; print the name of each linked file. |

| --help | Display a help message, and exit. |

| --version | Display version information, and exit. |

About The --backup Option

When using the --backup (or -b) option, the default file suffix for backups is ‘~‘. You can change this, however, using the --suffix option or setting the SIMPLE_BACKUP_SUFFIX environment variable.

The CONTROL argument to the --backup option specifies the version control method. Alternatively, it can be specified by setting the VERSION_CONTROL environment variable. Here are the values to use for either one:

| none, off | never make backups (even if --backup is given) |

| numbered, t | make numbered backups. |

| existing, nil | numbered if numbered backups exist, simple otherwise. |

| simple, never | always make simple backups. |

If you use -b instead of --backup, the CONTROL method is always simple.

If you specify the -s option (which symlinks), ln ignores the -L and -P options. Otherwise (if you are making hard links), the last option specified controls behavior when a TARGET is a symbolic link. The default is to act as if -P was specified.

ln examples

ln public_html/myfile1.txt

Create a hard link to the file public_html/myfile1.txt in the current directory.

ln -s public_html/myfile1.txt

Create a symbolic link to the file public_html/myfile1.txt in the current directory.

ln -s public_html/ webstuff

Create a symbolic link to the directory public_html named webstuff.

ln -s -b file1.txt file2.txt

Creates a symbolic link to the file file1.txt named file2.txt. If file2.txt already exists, it is renamed to file2.txt~ before the new file2.txt symlink is created.

Related commands

chmod — Change the permissions of files or directories.

link — Create a hard link to a regular file.

ls — List the contents of a directory or directories.

readlink — Print the value of a symbolic link or canonical file name.

unlink — Remove a file.

Linux and Unix ln command